Crowley Completes Kotzebue Dock Project to Serve Community for Decades to Come

Every spring in the remote Northwest Alaska community of Kotzebue, the huge sheets of ice covering Kotzebue Sound begin to crack and break. Massive chunks of 4-foot thick ice are carried by the powerful currents of the Kobuk and Noatak Rivers as they converge and spill into the Sound to the west of the Baldwin Peninsula.

As the ice travels with the current, it scrapes and grinds violently along Kotzebue’s only fuel and cargo dock, which stands like a sentinel between the Sound and the town, taking the brunt of the changing season and the powerful westerlies that blow in from the Arctic Ocean. Decades of brutal seasonal damage, as well as typical wear and tear caused by time and use, have taken their toll on the 50-year-old dock.

Right: Local contractor Drake Construction puts the finishing touches on the newly completed dock, placing rip rap rocks at the intersection of the north end of bulkhead wall where is meets together with the city’s concrete-armored beach mat. The heavy rock provides protection for the wall and a transition for the ice moving along the beach face.

In mid-October, Crowley Fuels, the current owner of the infrastructure, completed an extensive renovation project, expanding the dock by 30 feet, adding additional safety features, and fortifying it against the elements, with the expectation that the investment will serve the company and the community for many years to come.

“The expanded, fortified dock will support the region’s need for fuel and cargo supplies for multiple generations,” said Crowley’s Carrie Godden, vice president, safety, facilities and compliance. “We congratulate the women and men who made the design and construction of this valuable asset a reality. We also appreciate the community support and guidance as we completed the project, which serves the needs of fuel customers, other commercial carriers and the residents who count on its use for their food, materials and equipment.”

“Over the decades of use, the basic structure simply reached the end of its useful life and needed to be replaced”

Jed Dixon, project manager, Crowley facilities engineering

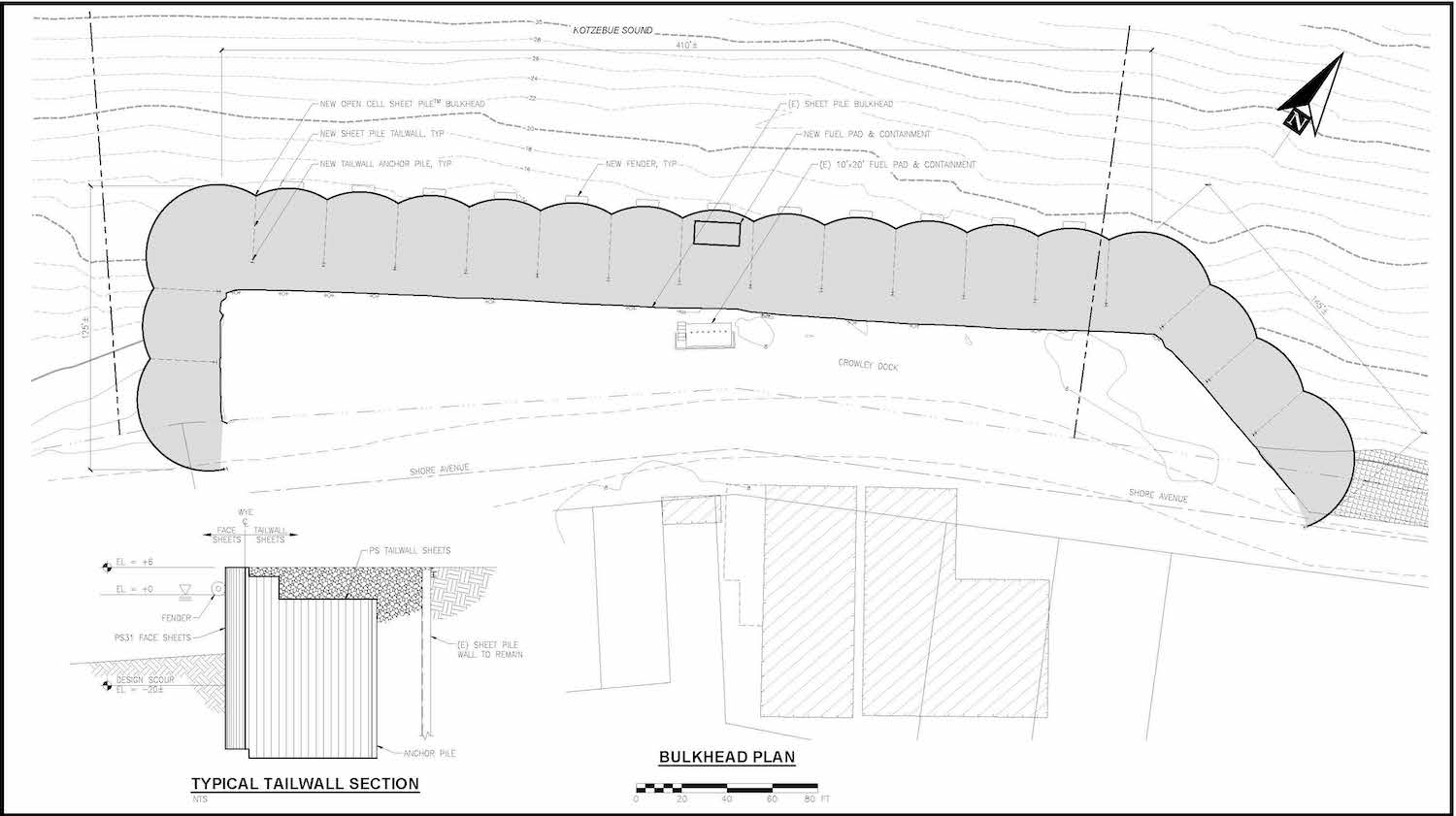

To minimize risks, improve safety and expand working space, the new dock was designed to encapsulate the old dock. The conceptual drawing at left shows the footprint of the new dock in relation to the old. Design and construction inspection services were provided by PND Engineers Inc.

A Critical Lifeline

As there are no roads connecting Kotzebue to the rest of the state, the dock infrastructure is a critical lifeline not only for the approximately 3,300 people of Kotzebue but also the residents of the many villages located around northwest Alaska. Each spring, once the ice has broken up enough to allow safe passage, Crowley, one of Alaska’s largest fuel distributors, brings in the fuel the communities need to keep homes warm, businesses operating, and boats, planes and vehicles running throughout the coming year.

“Nearly all freight and fuel that comes into the region is first delivered to the dock. It is an essential staging and transshipment point for goods coming into Kotzebue and the surrounding communities, and has grown to meet the needs of the community over time,” Dixon said.

Right: Alaska Marine Lines offloads its landing craft Nunaniq at the south end of the dock. Regular cargo deliveries for Kotzebue continued throughout the summer while construction was in progress.

At least twice each open water season, a Crowley-chartered tanker brings fuel into the deep water of Kotzebue Sound, and anchors about 10 miles offshore. Crowley’s local tug AKU, with its two 120-foot barges, meets the ship offshore and, over a period of days, transloads and delivers the fuel from the ship to the dock. At the dock, the fuel is transferred into Crowley’s 6.1-million-gallon fuel storage tank farm via the cargo header and pipeline system built into the dock.

After filling the tanks at the start of the season, the process is reversed and the fuel is transferred back into the AKU’s barges for delivery to the villages far up the shallow waters of the Kobuk and Noatak Rivers. Deliveries upriver must be done as quickly and efficiently as possible. Once the spring ice breakup is over, the water level in the rivers start to fall, eventually making it difficult, or impossible, for the barges to reach the farthest upriver communities to load their fuel tanks. When that happens, the only option for these communities to refill their tanks is to fly in fuel on an aircraft equipped with bulk fuel bladders – an expensive and risky solution.

In addition to fuel, the dock is used for general cargo by Alaska Marine Lines (AML) and other companies, which bring in necessary supplies ranging from food and vehicles to construction materials and equipment. The cost of goods is already high in these remote Alaska communities, and the dock facilitates the more economic method of delivery via water, avoiding the need to bring items in by air, which increases costs exponentially.

“The dock is important infrastructure for Kotzebue and the entire region; all goods come through here,” said Siikauraq Whiting, a lifelong Kotzebue resident. The dock is also a prime lookout for wintertime sled dog and snow machine races, and a good place to watch the ice go out in the spring, she added.

Planning for the future

While impressive to watch, the ice break-up event is incredibly stressful on the dock, eroding away the gravel, punching holes in the weakened steel, and creating gaping holes up to 12 by 16 by 25 feet behind the bulkhead wall, requiring extensive repairs each year.

Left: Erosion damage on the north face of the old dock, caused by spring breakup ice. Westerly storms coming off Kotzebue Sound also cause erosion damage to the dock face.

In 2017, after years of repeated erosion and damage to the dock, it became clear to Crowley that something must be done to ensure that the dock could continue to serve the needs of the company, the community and the surrounding region. The danger of a catastrophic failure was growing with each passing year.

The Crowley team, with consultation from PND Engineers, spent the next year identifying and evaluating a multitude of options. “We studied every possible scenario looking for the optimum choice, and ultimately decided to enclose the existing dock and build out new with additional safety features,” Dixon said.

As part of the planning process, Crowley participated in a series of presentations to the Alaska Native Village of Kotzebue, Northwest Arctic Borough Assembly, the Kotzebue City Council, and their respective planning commissions, and made a concerted effort to hear from community leaders and residents about their ideas and concerns around the dock.

Crowley reached out within and beyond Kotzebue to a broad range of organizations serving the Native peoples of the region, including NANA Regional Corporation, city and tribal organizations of all villages in the region, health and social service provider Maniilaq Association, the Northwest Arctic Borough School District, the Alaska Whaling Commission, and other subsistence organizations that could potentially be impacted by the project.

“I really appreciate Crowley and their outreach. Not every entity will put in the effort to get community input,” Whiting said. “The dock belongs to Crowley, but it is part of the community.”

“In most ports in Alaska, docks like this are publicly owned, built primarily to boost the economic development of the community. In this case, the dock is privately owned and operated by Crowley in its fuel business, but it is also used by commercial and contract carriers for non-fuel cargo, destined for the town’s government, businesses and private citizens. That puts the responsibility on Crowley to maintain infrastructure that is a rare hybrid: privately owned, but effectively a public good,” Dixon said.

“With a very short four-month navigation season and a large amount of cargo transferring across the dock, efficiency is very important, and this presents challenges both for regular operations and the reconstruction work,” he added.

“We need to make sure people are safe”

Safety was a top concern voiced by community members. During the winter, the ice in front of the dock becomes a highway of sorts for residents on snow machines, and limited daylight and winter storms often result in poor visibility.

“The dock project will move the trail on the ice further out. We need adequate lighting to make sure people can see the infrastructure. We need safety measures to make sure people are safe,” Whiting said.

Emergency access at the dock face was another concern the community asked Crowley to address. In the open water season, personnel that may fall in the water near the dock need a means of getting out safely. During the winter, snow is plowed off of the dock, and when the spring thaw begins, dangerous crevices may appear between the snow berms and the dock, potentially creating a situation where emergency crews need the ability to get into the water at the dock face.

Right: Local contractor Drake Construction displaces the water in the new cells with clean gravel fill. More than 12,000 cubic yards of gravel were required to bring the final grade to the same level as the old dock. Placement was done in “lifts” to protect the integrity of the sheet pile structure.

Left: Barge hauled out for winter storage, illuminated by new LED lighting.

In response to community feedback, Crowley erected 40-foot light poles with three industrial-strength LED light fixtures to illuminate the ends of the dock. Ladders were also installed in three areas along the dock face, providing safe access to and from the water.

“The entire neighborhood will benefit from the project with the extra lighting the dock has provided during the winter months. Typically, there is not a lot of light in the area so the 40-foot lights added much more of a safety measure during the winter, especially during storms,” Whiting said.

Protecting the Sound

Right: Pile bucks and crane operator with Swalling General Contractors “stab” a 40 foot sheet pile prior to driving the pile to depth.

Protecting the waters and wildlife of the Kotzebue Sound was also a top priority for Crowley. “The community is very dependent on the environment of the area and its resources for subsistence. This was a significant factor in our construction planning,” Dixon said.

“The Kotzebue Sound is extremely important to the communities on its borders. 70 percent of the food people hunt, fish and gather comes from the Sound. It is a critical part of people’s way of life and nutrition,” said Alex Whiting, director of the Native Village of Kotzebue’s Environmental Program.

Before construction could begin, Crowley completed an extensive federal permitting process. Working with PND Engineers and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), Crowley gathered biological data, identified at-risk wildlife, and formed a marine mammal management and mitigation plan to minimize negative impacts.

The plan included establishing marine mammal observer posts during construction at three locations around Kotzebue and hiring observers to watch for wildlife. If animals came within 10 meters of the worksite – called the level A harassment zone – work would be shut down temporarily. According to Dixon, during the course of the project, it never became necessary to shut down operations due to wildlife because the protected species stayed well outside this zone.

“The project seems innocuous as far as impact to the marine mammals,” Alex Whiting said. “Crowley is trying to mitigate harm to marine mammals, and the ancillary benefit is that someone is documenting marine mammal sightings. That additional information is helpful when trying to understand marine mammals in these parts,” he added.

Minimizing and monitoring noise

Left: Sheet pile construction closes in to the beach at the south end of the dock. An APE model 200-6 vibratory hammer proved effective in driving the piles, while minimizing disturbance to nearby homeowners and marine life.

To minimize the effect of construction noise on marine mammals in the area, Crowley specifically requested that the contractor use a vibratory hammer, which generates much less noise than the more typical impact hammer often used for similar pile-driving work.

Using vessel-based hydrophones for sound source verification and an anchored hydrophone array for passive acoustic monitoring, Crowley recorded construction activity noise underwater at different distances offshore, as well as the sounds of animals transiting in the area. Over the months ahead, NMFS scientists will compare the sound data with the visual animal sightings to discern if and how the construction activities may have affected them.

“We collected data on the sound pressure levels and monitored mammal behavior, paying special attention for harmful impacts. None were observed, and as a bonus the type of hammer we used was quiet on our neighbors and completely effective for the work we needed to do,” Dixon said.

Siikauraq Whiting, who lives next door to the Crowley fuel facility, particularly appreciated the extra effort that went into minimizing construction noise. “The last time they re-did the dock, there was lots of pounding. It’s quieter this time, a lot friendlier to the ears. We could feel the vibration but not hear the sound,” she said.

Expanded dock, expanded opportunities

Right: Construction of sheet piles cells reaches the half-way point. Construction activities needed to be tightly coordinated with dock users throughout the summer. [photo credit: Brian Ward and John Reid of Alaska Marine Lines]

The multi-million dollar dock follows the same footprint as the current one, while building over it and expanding out by 30 feet. The dock shape is based on PND Engineers’ proprietary “Open Cell Sheet Pile” design, a robust and durable dock solution used in dozens of locations throughout remote Alaska, from the Aleutian Chain to the Arctic Coast. The new dock also features ship-class bollards and barge fenders.

Working with Anchorage-based Swalling General Contractors, Crowley constructed 14 “cells,” each 35 feet in width, by driving 40-foot long sheet piles into the sea floor with the vibratory hammer. Kotzebue-based Drake Construction then filled the cells with gravel following a strict loading and compacting process, then graded and compacted the finished dock surface.

“That makes it a very strong structure,” Dixon said. “When you have the sheets driven deeply enough into the seafloor, the current isn’t going to get under the structure to undermine it.”

Building the dock 30 feet out into deeper water allows access for larger vessels. “We haven’t been able to bring in larger vessels mainly due to the presence of two shoal areas near the mouth of the channel. Although that will continue to be a limiting factor for some time, having the new dock built out into deeper water makes it possible for larger vessels to access the dock, improves operational flexibility for Crowley, and opens up opportunities to the community for future economic development,” Dixon said.

The expanded design creates new space on the upland side of the dock, providing additional area for cargo operations, and a wider buffer to separate vehicular and pedestrian access from Crowley’s working area, enhancing safety for both the employees and the public.

The project also provided the opportunity for Crowley to work with the city to address several long-standing property encroachment issues, created by the growth of the community around the fuel facility over time.

“Our facility has been there since the 1950s under one owner or another. It was once in a remote area, but then the community grew up around it,” Dixon said. What used to be open land around the fuel facility is now filled with residences, the high school, lots of pedestrians and vehicle traffic – even one of the town’s main roads, Shore Avenue, which runs through Crowley’s fuel facility.

“Crowley encroaches on city property, and the city encroaches on Crowley property,” Dixon said. “We are negotiating a deal to reconcile the property issues with the City as part of the dock project.” To date, this process has resulted in the transfer of a portion of land at the north end of the dock to Crowley, with the settlement of four remaining parcels soon to follow.

An investment in the community

Left: Crowley’s 120 series barge and the tug Aku tied up alongside the newly built north end of the dock. Depths alongside the north end range from 4 feet near shore to 20 feet offshore, effectively creating a new berth for vessels.

With winter on its way, Crowley wrapped up the dock expansion project on schedule in mid-October. With thoughtful planning, quality construction and proper ongoing maintenance, Crowley expects the new dock to stand ready to serve the community for the next 30 to 50 years.

“The community benefits and Crowley benefits. It’s a win, win,” Siikauraq Whiting said.

“It’s an investment Crowley is making back in the community,” Dixon said. “We’re here for a long time.”